Jane Whittle

Late medieval books of hours provide a wealth of attractive illustrations, apparently of ordinary people going about their work across the agricultural year. Conventionally, books of hours begin with a calendar of Christian festivals illustrated with the labours of the months and the signs of the zodiac. In this blog I re-examine some of these ‘labours’, making comparisons with initial findings of the ‘Women’s work in rural England 1500-1700’ project, looking particularly at the gender of workers, and the seasonality of activities.

For the historian of rural England, the basic question is: how far can these images be taken to illustrate English rural life, rather than that on the continent? Some elements are clearly alien, such as viniculture, and the architecture of Flemish farmhouses. But collecting firewood, shearing sheep, mowing hay, harvesting grain, ploughing and sowing, and the slaughtering of animals – all staple images from the books of hours – were also essential activities for the inhabitants of rural England. It is on these activities that I focus here.

April, Da Costa Hours

Most late medieval books of hours were produced in Flanders and France. The workshop of Simon Bening in Bruges, Flanders, produced a series of particularly captivating hours in the early sixteenth century such as the Da Costa Hours (c.1515)[1]; the Hennesy Hours (c.1530)[2]; and the ‘Golf’ Book (c.1540)[3]. Those from France are less uniform and tend to be slightly earlier. Here I have consulted the famous Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c.1410)[4] and the Hours of Henry VIII (c.1500)[5], as well as a panel of the 12 labours of the months from a manuscript edition of Pietro de Crescenzi’s Book of Rural Benefits, produced in 1459[6] – not strictly a book of hours, but following the same illustrative conventions.

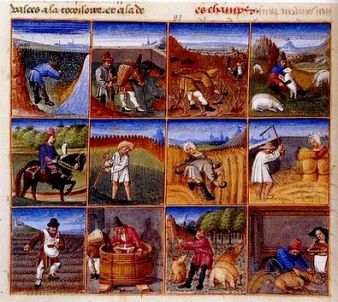

Panel from Pietro de Crescenzi Book of Rural Benefits, 1459

The women’s work project has collected largely incidental evidence from court depositions about work activities: specific people recorded carrying out specific work tasks. The evidence was drawn from the south-west of England for the period 1500-1700. The dataset I am analysing here contains 4000 tasks representing all types of work including housework and care-work. The 4000 tasks recorded are biased towards men’s activities – 71% were carried out by men in comparison to 29% by women. This seems to be because men acted more often as deponents. In the discussion below I sometimes mention a ‘compensated’ figure – which is arrived at by multiplying the number of work tasks undertaken by women by 2.4, a calculation which creates a 50/50 balance of tasks between men and women overall.

Providing firewood

January, the ‘Golf’ book

January is conventionally illustrated with images of eating and keeping warm. A cut-away effect allows us to view families inside the farmhouse huddling inside next to the fire: women get on with their spinning (the Hennessy Hours) or hold babies (the Golf Book), while men and women outside prepare more firewood. How was the provision of firewood gendered in the database? We found that working with wood (cutting wood from trees, loading and transporting it, chopping wood) was largely a male task: out of 97 examples only 13 were carried out by women – but as illustrated in the ‘Golf’ Book, when women were involved, they were mostly fetching and carrying wood, as well as buying and selling firewood. In terms of seasonality, November, December and April were the peak times for gathering and transporting wood, while February and March were a low point. Thus the dominance of cutting wood in images for January seems to result from the aim of depicting the coldest month of the year, rather than from the fact more wood cutting took place in that month.

Shearing Sheep

July, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

Several images of sheep-shearing from France depict women carrying out this task, but in the Flemish books of hours it is always done by men. Sheep shearing illustrates various months from April (Crescenzi Book of Rural Benefit), through to July, with June being most common. The database records 38 people specifically engaged in shearing sheep, 8 of whom were women. If we compensate for the under-recording of women, this suggests that around two-fifths of sheep-shearers in SW England were women.

Interestingly, in all 8 cases these women were working for some-one else, suggesting some professionalisation of the role. May and June were the peak times for shearing, with only one case recorded in July, and none in April.

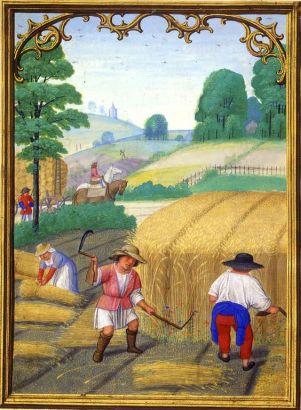

Harvesting Hay

Mowing hay is depicted in June in the French illustrations and July in the Flemish ones. When they show more than one person at work, all show both men and women busy in the hay harvest, but engaged in different tasks. Men mow the hay with a scythe, while women rake it into heaps and turn the hay to allow it to dry in the sun. A successful hay harvest was weather-dependent: sunshine was needed to dry the crop so that it could be stored and kept, rather than rotting. This is one reason for a later hay harvest further north in Europe. There were 55 cases of people working in the hay harvest in the database: July was the peak month, but June was also common. There was also some hay-making in August and September – most likely for a second crop or ‘after-math’. The hay harvest did indeed involve women and men: there are 42 men recorded and 13 women. If we compensate for women’s under-recording, the proportions work out at 58% male and 42% female workers. Mowing was only done by men, but most workers are recorded as ‘making hay’ which seems to describe the whole process of harvesting from mowing to carting.

June, Hours of Henry VIII

Harvesting Grain

July, Hennessy Hours

In books of hours the wheat harvest is depicted in July and August. Men and women are shown in the fields together, but often it is only men who are cutting the crop. It is worth paying careful attention to the harvest implement being used. Both men and women used the sickle, as shown in the illustration from Crescenzi’s Book of Rural Benefits above, and also, for instance, in the early 14th century English Luttrell Psalter. But the implement being used in all the Flemish books of hours discussed here, is a Hainault scythe, which was more efficient than the sickle, and appears, like the full-sized scythe, only to have been used by men. Women still worked binding the sheaves, as shown in the Da Costa hours, below.

August, Da Costa Hours

The Hainault scythe was not used in England, where wheat and rye were typically reaped with a sickle, while barley and oats were mown with a full-sized scythe. In the database we recorded 65 cases of people harvesting grain, of whom only 6 were women. Five of the women were reaping wheat or rye with a sickle, while one was engaged in unspecified harvest work. Of the men, 36 were reaping wheat or rye with a sickle, 13 were mowing barley or oats with a scythe, and 10 were engaged in unspecified harvest work. If we compensate for the under-recording of women, 20% of the workforce was female. The month in which the work was carried out is not often recorded, probably because the harvest itself was seen as a sufficient indicator of the time of year. However, in 6 cases the work was specified as taking place in August and in 10 cases September, later in the year than the books of hours suggest

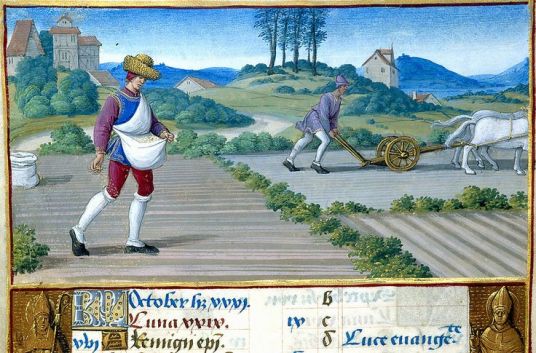

Ploughing and Sowing

September, Hennessy Hours

Ploughing, sowing and harrowing are always depicted as done by men, both in the French and Flemish images. Most commonly these activities illustrate the month of September, but sometimes October, and occasionally March (e.g. in the Très Riches Heures, in preparation for spring-sown crops). In the illustrations examined here the ploughs were all worked by one man, and all except those in the Très Riches Heures were pulled by horses rather than oxen. In early modern south-west England ploughs were typically pulled by oxen, and worked by two people, one leading the oxen and the other driving the plough. The database recorded 45 people engaged in ploughing and tilling. One of these was a woman, in Somerset in 1551, who was described as ‘helping to plough’, almost certainly leading the oxen. Also surprising was that of the 11 people described as sowing grain, 3 were women, suggesting this was not an altogether unusual thing for women to do, despite the lack of visual evidence. Ploughing, tilling and sowing was spread across the months of September, October and November, and then resumed in February, March and April, with more cases recorded in the database for Spring than Autumn.

October, Hours of Henry VIII

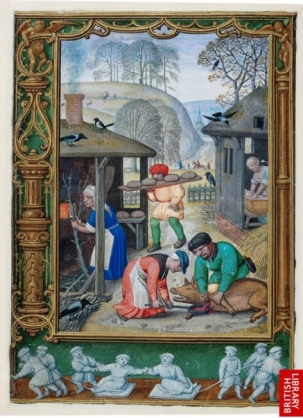

Slaughtering pigs

December, the ‘Golf’ Book

The end of the labours of the months in the books of hours came with the slaughtering of a pig in December in preparation for Christmas feasts. The Da Costa Hours and the ‘Golf’ Book both depict a man killing the animal, while a woman catches the blood in her frying pan (something similar is happening in the Crescenzi Book of Rural Benefits). In the ‘Golf’ Book another woman in the background is kneading bread, a man carries bread to the oven, and a third woman feeds the fire, ready for baking. The project didn’t find many examples of pig slaughter – just 4 cases, three done by men and one by a woman. There were also two cases of ‘dressing a pig’ (not some weird fancy dress ritual, but the processing of the meat for consumption or storage), one by a man and one a woman. These were concentrated in October and November, rather than December. There were many more cases of killing and dressing sheep – 81 in total, 7 of which involved women.

So do books of hours provide an accurate depiction of rural life? Such rich visual evidence should not be ignored, and if used carefully they are a useful tool for bringing to life written evidence from England. But we must bear in mind the fact that farming technology and seasonality varied across northern Europe. The sheep-shearing example also indicates that the gender division of labour in some activities varied by region. It would be great to have studies of work tasks similar to ours with which to compare the gendering of work in SW England with that in Flanders and northern France.

But the biggest cautionary note should be reserved for what the books of hours do not show. Of the 4000 work tasks recorded in our database, over 1000 related to commerce (buying, selling and going to market), over 400 to transport, and over 350 to crafts and textile production. We only get glimpses of these activities in books of hours. For instance the October scene in the Da Costa hours shows men haggling over the sale of a bullock. Women are occasionally shown spinning. Carts are shown transporting hay and grain on the farm. Sheep are driven out of the farm in springtime. The Da Costa hours also has the only ‘labours of the month’ illustration I know of dedicated to textile production. November shows two men and a woman processing flax ready for spinning and then the production of linen cloth, a speciality of Flanders. In Devon and Somerset it was turning wool into heavy woollen cloth that took up so much men’s and especially women’s time in rural communities.

*Some other images of women’s work from this period are discussed in a series of posts on ‘the many-headed monster’ blog, here*

[1] Now owned by the Morgan Library in New York (MS M.399)

[2] Owned by the Royal Library of Belgium in Brussels (KBR MS II 158)

[3] At the British Library (Add MS 24098) (viewable online here)

[5] At the Morgan Library (MS H.8)

[6] Now held of the Musée de Condé in Chantilly (MS 340)

Haymaking (mowing): two crops: prima vestura and secunda vestura.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In southwestern rural France prima vestura and secunda vestura are still practiced in June and in late July/August respectively, depending on the weather. Even though tractors are now used, the cut hay still lies on the field for several days to dry before being gathered and baled (plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose).

Interestingly, I have never seen any women involved, which suggests that the task has become more gender restrictive.

In the case of cows, the drying is very important because any moisture leads to mould which not only can sicken the animal but also changes the taste of the milk. Already hay makes winter milk taste slightly more bitter than summer milk even though the “hay” is essentially the same grass they eat in summer, only dried. Hence the early modern recipes for “spring” butter and “spring” cheese when the cows are eating the first grass in the fields.

In addition to moisture, hay can contain toxic plants. “Hay” is basically everything growing in the meadow that is cut and dried for winter fodder. It includes all the other wild flowers and weeds growing amongst the tall blades of grass. Some, like hemlock, tend to lose their toxicity when dried. But others like dog mercury keep their poison. So the farmer tends to keep an eye on what is growing in each parcel before he cuts it for hay. I wonder if part of the women’s job as they raked was to remove any unwanted plants. Have you come across any mediaeval or early modern texts mentioning this?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Workers of the Week: Harvesters | Women's Work in Rural England, 1500-1700