Mark Hailwood

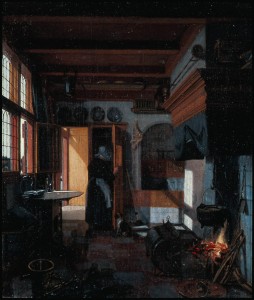

Kitchen Interior, by Emanuel de Witte (Dutch, 17thC). Source: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Credit: Seth K. Sweetser Fund

As Jane discussed in our previous post – ‘What is Work?’ – women’s work in early modern England is often assumed to have been principally ‘domestic’, taking place within the home and consisting mainly of childcare and housework. One key aim of our project is to uncover as much information as we can about such ‘domestic’ work, and to give it its due as an important and productive part of the economy. At the same time, however, we think it ‘unlikely that these tasks would have taken up the majority of most women’s time in the early modern economy’, as Jane puts it. Another key aim of the project then is gathering evidence of the full range of work activities that women undertook. In this post I will consider the extent to which these might have included agricultural tasks.

It is well known that across the country women played a crucial role in production for England’s major industry, the cloth industry, by spinning.[1] If such work usually still took place in a domestic setting we know from important recent research that women in urban areas were often heavily involved in more ‘public’ work activities – especially retailing in markets, shops and public houses.[2] But what about women in rural areas? Was women’s work in the countryside more clearly confined to the domestic sphere, with agricultural work activities overwhelmingly dominated by men? The gendered division of labour in rural areas has received less scholarly attention than the urban context, despite the fact that this would have been the majority experience at this time. For this reason our project takes rural England as its focus.[3]

We are in the very early stages, but one notable feature of the archival material I have been working with so far is the prevalence of examples of women involved in agricultural work of various kinds. For instance at Instowe, North Devon, in 1634, between Whitsuntide and Midsummer, Margaret Pugsleigh, Agnes Horwood and Joane Wilkey were ‘at weeding of corne’ in a field when Joane Wilkey defamed her mother. Agnes Clement of Midsomer Norton, Somerset, was sent for in July 1607 to come and ‘wynnoe corn’ ‘whilest the wynde did serve’, only for her employer to sexually assault her when she arrived to undertake the task.

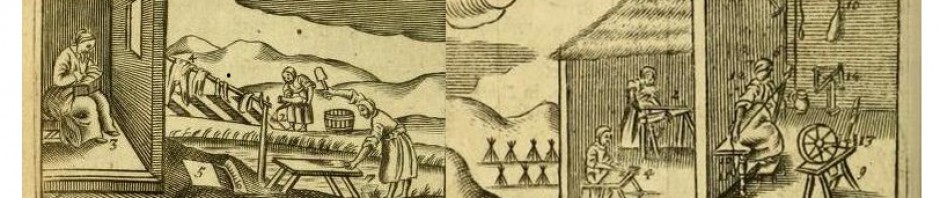

As I say, we are dealing with a small sample at the moment, but women’s involvement in agricultural activities is also attested by visual evidence from the period (and I would argue that, contrary to a recent blog post by Brodie Waddell, there are plenty of images of women at work from the early modern period – and we will be showcasing as many as we can in our blog posts). A number of ballad woodcuts show women at work in the fields (something I have discussed in a blog post elsewhere), as do the rich offerings of the Brueghels (below), and native English landscape paintings such as Edward Haytley’s The Montagus at Sandleford Priory (1743).

What such depictions tend to show is the involvement of women in agricultural work around harvest time: a time of the year when the whole community, including men, women and children, focused their energies on bringing in the crops – and possibly a time when the usual gendered division of labour was temporarily realigned. It will be interesting as we gather more data to explore the seasonal patterns of women’s involvement in agricultural work, but whilst the period of the corn harvest (roughly from 1st August to mid-September) will undoubtedly reflect changes to the working patterns observed throughout the rest of the year, I would not expect us to find that women’s involvement in agriculture was restricted to harvest-related activity alone.

Indeed, the examples I have cited above, of weeding and winnowing corn, took place earlier in the summer than the corn harvest proper, and although we might classify them as summer field work they were not part of the harvest itself. Moreover, the evidence I have worked with so far indicates that women engaged in a much wider range of agricultural activities than just summer field work. In June of 1620, for instance, Grace Welsh of St David’s, Exeter, helped her husband to drive three heffers from Woodbury to Crediton Market. Alice Kingston of St Edmund’s, Exeter, testified to milking ‘kine’ (cows) in 1634. Anne Josse and Wilmota Smalridge, both from the village of Dunsford on the eastern edge of Dartmoor, together undertook the yearly task of shearing fifty sheep for one Mr Westcott between 1632 and 1634.

Women’s involvement in agricultural work was not just a product of needing ‘all hands on deck’ during the rush of harvesting. But what was it that determined the types of agricultural work they did or did not do? This will be another question we will be thinking carefully about as we look to identify clearer patterns in our data, but again I’d like to offer one or two initial thoughts. Most obviously we might expect a division of labour in which men carried out those tasks that most required physical strength and technical skill. This undoubtedly is part of the story, but again the examples we have suggest it is not the whole story. For one, we might well expect sheep shearing to be the kind of skilled task that would be the preserve of men, but clearly it was not.

Women were also involved in demanding physical work: in June of 1556, at Ilsington, Dartmoor, servant Wilmota Rogers was ‘pitching hay up’ to her master in his hay-loft, a job we might expect to be the remit of male rather than female servants. Nor is this example unique: in 1607 another servant, Elizabeth Brown of Misterton, Somerset, was ordered by her master’s son to ‘throw sheaves to him’ in his hay-loft. Agnes Parker of Chilton Cantelo, Somerset, was crossing a bridge in 1592 with a measure of hay on her head and a pot for milking in her hand, when she was tragically blown off the bridge by a gust of wind and drowned in a ditch. It seems clear enough that women were involved in at least some of the agricultural tasks that required a good deal of strength, such as the carrying and throwing involved in moving and storing hay. Any neat boundaries between women’s tasks and men’s tasks blur further still when we consider that weeding corn was an activity done by both women and weaker men, and that winnowing seems to have been a job for women in the south west of England, but a task done by men in the east of the country.

As the project progresses we will be gathering significant quantities of data on women’s work activities that will allow us to make some far more concrete conclusions about the gendered division of agricultural work than the handful of examples and images I have discussed here. That said, I think we can already see a number of key research questions emerging—about the seasonality, range, and types of women’s agricultural work—that may not lead us to the answers one might most obviously expect; and at least one clear conclusion: that agricultural work of various sorts was indeed an important component of women’s work in rural early modern England.

[1] Craig Muldrew, ‘”Th’ancient Distaff” and “Whirling Spindle”: measuring the contribution of spinning to household earnings and the national economy in England, 1550-1770′, Economic History Review, 65:2 (2012), pp.498-526.

[2] See, for instance, Marjorie McIntosh, Working Women in English Society, 1300-1620 (Cambridge University Press, 2005); Tim Reinke-Williams, Women, Work and Sociability in Early Modern London (Palgrave, 2014).

[3] For some consideration of the gendered division of work in rural areas see Amanda Flather, Gender and Space in Early Modern England (Boydell, 2007).

Sad but not surprised to read of Agnes Clement being sexually assaulted by her employer. Because a lot of your data comes from courts/magistrate records might it be possible to form a view as to how many such incidents were reported and how seriously they were taken?

LikeLike

Thanks for your question Moira. There are an awful lot of cases of sexual assault in the records we are using, yes. In a sense their frequent appearance before the courts shows that they were taken seriously by the legal system (rape, for instance, was a felony, and hence punishable by death), but historians tend to think that such incidents were, then as now of course, massively under-reported. In one particularly shocking case (that I have talked about in another blog post: https://manyheadedmonster.wordpress.com/2014/12/08/alehouse-characters-4-the-good-fellowette/) that took place in an alehouse in Snargate, Kent, in 1602, a group of male drinkers gang-raped a serving maid who died from the injuries inflicted. When this appalling crime was first reported to the local magistrate he initially dismissed it as ‘but a trick of youth’. The case eventually came to trial, but this reaction is a stark reminder of how brutally misogynistic the application of the law could be, even when the letter of the law took such offences seriously.

The extent of sexual assault is not something we are focusing on specifically in this project, but other historians have and do use this kind of material to address these sorts of questions. Dr Garthine Walker at Cardiff University, for instance, is currently doing a research project on rape in early modern England, more on which can be found here: https://garthinewalker.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

Pingback: The Clip: May 19, 2015 | West by Midwest

Pingback: Women’s Work in Rural England, 1500-1700 | the many-headed monster

Pingback: History Carnival 146: Facets of Environmental History | NiCHE

Pingback: History Carnival: Facets of Environmental History | Historical DeWitticisms

Pingback: Women’s Work in Rural England, 1500-1700 | Gender and Work in Early Modern Europe

Pingback: Workers of the Week: Winter is Coming | Women's Work in Rural England, 1500-1700

Pingback: Why do women carry things on their heads? | Women's Work in Rural England, 1500-1700

Pingback: Workers of the Week: ‘Ploughmen go whistling to their toils’ | Women's Work in Rural England, 1500-1700