Charmian Mansell

Last month, the Women’s Work team celebrated the launch of our new digital edition of Quarter Sessions and Church Court depositions (you can find it here).During my time on the project, I spent several months selecting, transcribing, annotating and coding this material and it’s a real pleasure for me to finally see the fruits of this labour. The resource contains 80 fully transcribed and annotated depositions relating to a selection of 20 cases from across South West England. These depositions have been at the centre of our project and are an essential resource for anyone interested in the social, economic and legal environment of early modern England.

The Drowning of Henry Abbott

In celebration of this launch, this latest instalment of our project blog focuses on the case of Henry Abbott of Bridgwater in Somerset. The depositions of this case can be read in full here.

Early one September morning in 1650, five men of Bridgwater (Somerset) – Richard Weekes, Henry Abbott, Thomas Robinson and his two sons – entered Richard Glover’s field to reap corn. Upon arriving, it began to rain and so they returned to the town and drank beer in the house of one William Wookey, which cost them 15d. As the weather improved, the men returned to the field, but Henry Abbott remained behind and continued drinking. A can and a half of beer later, he too returned to the field as the men stopped work for breakfast. He told them that he had run into Richard Glover who had requested that they cut the corn lower and further.

As the men resumed their work, a woman named Joan Symonds and her young son, John, made their way across the field, carrying on their heads pails of grain which they had bought that morning from town. The beer fuelling him with confidence, Henry declared to his company that he was going to kiss the woman, ignoring Thomas’ warnings. He approached her and declared that ‘he must kiss her for he had made a vow so to do’. As a married woman, Joan attempted to refuse his advances, but Henry nonetheless kissed her and walked away laughing.

He hadn’t got far before he stumbled and toppled backwards onto the sand at the edge of the river. As he tried to return to his feet, he lost his footing again and fell into the water. Joan’s son, John, was the first to spot the man and cried out ‘Lord mother the man is in the river’. The men in the field dropped their reaping hooks and ran to the riverbank. But he was too far away and after several attempts to rescue him, they all watched helplessly as Henry Abbott disappeared beneath the water and drowned.

In early modern England, drowning was typically a matter for the Coroner’s Court, which dealt with accidental death. But we find this case among the records of the Quarter Sessions (the county court), where Joan and her son were examined, along with others who witnessed the unfortunate event. Joan’s anger at being propositioned by Henry presumably raised suspicions over whether Henry fell into the river or was pushed. Using depositional evidence like this has its challenges: we cannot know whether the depositions of witnesses are factual accounts of what took place or, as Natalie Zemon Davis has suggested, carefully-constructed narratives designed to achieve a particular outcome in court.

While they may be imperfect refractions of the events that took place on the banks of this Somerset river, they are nonetheless a record of the plausible. The events recounted by witnesses had to at least sound credible and therefore we can take from them incidental evidence of early modern behaviours, practices and experiences.

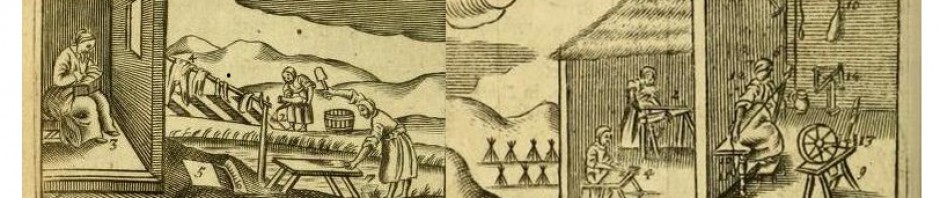

Importantly for our project, the case tells us about women’s work. Joan Symonds is travelling home from Bridgwater with her son, having purchased four pecks (a bushel) of grain. Both mother and son carry the grain home in pails on their heads, a skill which women (in particular) learnt at a young age, as explained here. Commerce (buying and selling), was part of women’s working activities, as was transportation of goods from place to place. We also get a rare glimpse into experiences of parenting and the type of work that a young boy was expected to do.

We also learn about the working patterns of male reapers: the workers assemble at 5am on that fateful September morning. Their work is postponed by the rain but they return when the weather is fairer. Thomas Robinson describes using a hook (also known as a sickle), a tool which was typically used to cut crops and had a short handle and curved blade. We get a glimpse into the dynamics of relations between employer and worker: Richard Glover, the cultivator of the field, was clearly not satisfied with the work that then men had begun, asking Henry Abbott to inform them that he wanted the corn cut lower and further, thereby improving his yield.

My brief exploration into the depositional accounts of Henry Abbott’s death offers only a glimpse of what we can glean from these rich documents. While depositions are freely available to view in local record offices, their accessibility is reserved largely for those with time to trawl such a vast archive and with the palaeographical skills to read early modern secretary hand. This new digital resource therefore makes this material accessible and we hope that this will be a valuable resource for those curious about early modern English society.