Overview:

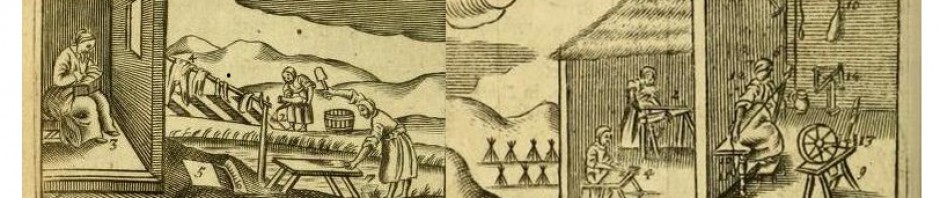

The starting point for this project is that we still know surprisingly little about the normal everyday experience of women’s work in pre-industrial England. While sixteenth-century commentators noted that women’s work ‘has never an end’, historians of pre-industrial England have struggled to move beyond generalizations and find systematic evidence of women’s activities. This project applies a new methodology which aims to illuminate the majority experience: unpaid work in rural households – as well as tracing forms of waged work – by gathering and analysing new evidence of women’s and men’s everyday working lives. Using a sharper definition of ‘work’ our project is focused on collecting incidental information about work activities from court documents for quantitative analysis, as well as data on waged work from accounts. It aims to systematically describe and explain the contours of women’s working lives in rural England between 1500 and 1700, making comparisons between women’s and men’s work, and paid and unpaid work. The results will have the potential, we hope, to transform key debates about gender and economic development in Western Europe before the Industrial Revolution.

Background Debates:

Classic and recent studies reveal the types of work women did in the rural pre-industrial economy, but do not quantify women’s participation in different activities. This means that the significance of women’s work to the economy is still uncertain. Yet a number of high-profile (and contradictory) historical debates now highlight the role of women’s work in economic development. For instance it has been argued that women’s mass participation in the wage labour force by 1500 was a key factor in western European economic development; that female workers were paid less because they worked shorter hours as a result of their caring duties at home; and that women entered the paid workforce in large numbers for the first time from the early eighteenth century onwards. None of these theories is backed up by sufficient historical evidence. Nor have historians been very clear about what they mean by ‘work’, overlooking the significance of unpaid labour to the wider economy. Historic patterns of women’s work are subsequently widely misunderstood. Ideas about women’s work in pre-industrial western economies vary from ‘golden age’ views suggesting women once did virtually every type of work, to an opposite assumption that women’s traditional work roles were restricted to housework and childcare. Despite the absence of accurate data, such views are used to support arguments about women’s role in the modern family and workplace.

Our Methodology:

In 1993 the UN revised its guidance on national accounting to include unpaid work within the home, in recognition of the fact that women’s work and work on small peasant farms was being grossly under-valued in estimates of GNP. It adopted a definition of work suggested by the economist Margaret Reid in 1934, of work as any activity that could be replaced with paid labour or purchased goods. The UN promotes time-use studies as the most effective way of collecting this data. Economic historians have yet to widen and sharpen their definitions of work in a similar manner. This project applies this definition of work to early modern England and adopts a methodology that mimics time-use studies. This will allow a large quantity of data measuring the prevalence of different work activities to be collected for the first time for early modern England, offering an unprecedented window into ordinary working lives.

Approaching the history of women’s work with the same methodology as men’s produces limited results. For instance, while many early modern documents describe men by their occupation, women are described as single, married or widowed. Instead, this project is collecting incidental evidence about work activities from manuscript court documents. This approach is not entirely untested: it was pioneered by Sheilagh Ogilvie in her 2003 study of early modern Germany and is currently used by Maria Ågren’s ‘Gender and Work’ project on pre-industrial Sweden. Here it is adapted and developed for the English evidence. Data is being gleaned from the documents of three types of court: church courts which dealt with disputes over probate, marriage and sexual behaviour; quarter sessions which were county-level criminal courts; and coroners’ rolls which record accidental deaths. These documents record the approximate time, place and nature of activities people were engaged in when an incident took place, as well as the names of the people concerned. Each court has a slightly different bias; using them together will balance the results.

Scoping exercises with samples of documents predict that a total of 5000 observations of work activities will be collected, of which at least 1200 will relate to women. The project is also collecting and analysing evidence of women’s waged work from household and farm accounts, providing an essential comparative element. Waged work recorded in the accounts of wealthy households has been privileged in existing studies, but we hypothesise that the work tasks and gender balance of this type of work was quite different from work in small farming households. Evidence will be collected from five counties forming a swathe of south and west England from Hampshire to Cornwall, selected because they contained a range of agricultural regimes and rural industries, some of which favoured women’s employment and some which did not.

You can read about our methodology in much more detail here.

Outputs:

In due course we will produce a series of articles detailing our results and expanding on our methodology, as well as giving various conference papers as the project progresses to test out our ideas about both – so watch this space!