Mark Hailwood

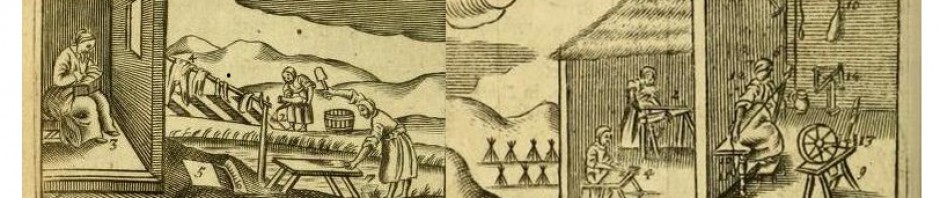

It’s time for another post in our recently launched ‘Workers of the Week‘ series, in which we highlight some appropriately seasonal examples of the work activities the project is finding. The focus this week, then, is on workers doing tasks designed to make ready for the onset of winter.

A significant number of our examples from late November and early December relate to the replenishing of wood supplies to fuel much-needed winter fires. On the 25th of November 1591, Thomas Ven, an 80-year-old husbandman of King’s Brompton in Somerset, was up a ladder pruning an oak tree with an axe when he plummeted to his death. Locals must have started to wonder if evil spirits possessed the wood of Barlynch Grove, where Ven had fallen, for in December of the following year the 28-year-old Edward Norman met his end by falling out of an ash tree that he had climbed to cut branches from.

One way to avoid the risk of falling from a tree was to cut the whole thing down – as Tremor Wylmot did to an oak tree in Eling parish, Hampshire, in November 1559. Of course, that brought with it the risk of being crushed to death as it toppled – the fate of poor Wylmot. The danger didn’t end when a tree had been felled either: William Hayes, a labourer of Hilmarton, Wiltshire, was sawing timber with his fellow labourer Edward Tiler, on the 5th of December 1597, in a sawpit, when a piece of timber fell on Hayes and killed him.

Much safer was the job of gathering-up bits of wood to fuel the fire: something Thomasine Weather of Uplowman, Devon, was sent to do by her mother at 5pm one December evening in 1597. She went to one ‘Henry Burnard’s ground called Butts Moore, about a quarter of a mile off’, to ‘fetch a burden of wood’ – perhaps not an enviable job though, given that it was likely to have been dark at the time. John Chorley of Tiverton was another Devonian who ‘went abroad for the fetching of a burden of wood’ after dark – heading to ‘a lane called the water lane’ at 9pm on the 11th of November in 1597. Perhaps these were desperate evening ‘fuel-runs’, triggered by a realisation that their wasn’t enough fuel on hand to keep the fire burning throughout a cold winter’s night.

As the cold and dark nights started to close in, thoughts turned to sources of light as well as those of warmth. ‘A little before Christmas Day’ of 1597, Mary Bower of Ugborough, Devon, sent her two children – Thomas and Dewnes (a uniquely Devonian girls name) – ‘to Thomas Blunt’s house for candles’. And Thomasine Weather’s widowed mother, Johane, stocked up by buying two and half pounds of tallow in December 1597 – one of the main uses for which was making candles (it was a cheaper alternative to wax).

To what extent were the work tasks associated with preparing for winter gender specific? Well, it seems as though wood-cutting of various sorts was largely men’s work – we haven’t (yet) got any examples of women felling trees or climbing them to cut off branches, but as we have seen, gathering wood was a job done by both men and women. Another common task for this time of year was the slaughtering of animals – both to provide meat for the winter months, and to save on the resources that would be needed to feed and house them during the cold season. Often this task was undertaken by a specialist butcher – invariably a man – such as William Froste of Colebrooke, Devon, who in December of 1597 was brought a sheep by fellow parishioner John Venycomb, who ‘willed [him] being a butcher to kill the same sheep and sell it for him’.

But there is plenty of evidence to suggest that both women and men often slaughtered their animals themselves. Phillipp Marshall, an oddly named widow of Bratton, Devon, confessed that on Christmas Eve of 1597 she had stolen a lamb which ‘her and her daughter killed and dressed [i.e. prepared for cooking] in [her own] house, to serve their great need’. They were clearly desperate to find something to grace the dinner table on Christmas Day. That same month and year one Alice Daie, a married spinner from Shobrooke, Devon, was likewise accused of having stolen a sheep. Alice insisted that the mutton found in her house was not criminally procured, but came from ‘a certain bad mazed sheep’ that she had bought for 16d from one Edward Brown – an animal ‘which was killed and skinned’ by her own hand in her own home. The skill of animal slaughter was not the preserve of specialist male tradesmen.

One might reasonably wonder, though, whether there is a ‘source effect’ at work here (a question we are constantly asking of all of our evidence). Perhaps women only slaughtered animals when they had stolen them? It would hardly have been prudent in a small community to take an ill-gotten gain along to the local butcher; much better to get it into the pot and boiled beyond the point of being identifiable as quickly as possible. It’s true that most of our examples of women slaughtering animals come from cases in which they are accused of theft, but the fact that they were able to do the task demonstrates that many women did possess the requisite skills. What is more, Alice Daie clearly didn’t anticipate that a jury would have thought there was something unusual or suspicious about a woman slaughtering her own sheep, or she might have thought harder about offering this as her defence.

So, as the men and women of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century rural England readied themselves for winter – gathering wood, stocking up on candles, putting animals to the slaughter – the division of labour did not neatly align with tidy distinctions between male work as skilled and female work as unskilled (something we also saw in a recent post on agriculture, which demonstrated women’s involvement in sheep-shearing). Like animal slaughter itself, the gendered division of labour was somewhat messier – although it does seem to be the case that women avoided the particularly hazardous task of wielding an axe at an oak or ash.